Communication and Change

One thing that President Trump understands is branding, although with “steel slats” I really think he’s losing his touch (panic will do that to you).

His more successful efforts have included MAGA, Crooked Hillary, Fake News, and, of course the Big, Beautiful Wall, compared to which Steel Slats is New Coke.

Branding is perfect for Trump, whose name is itself a brand, because a brand doesn’t require facts, logic, or any argument at all: just an impression.

This might be a lesson for corporations that have invested so much in creating and building their brands — not least by backing them up with actual goods and services.

Trump sees the power of a brand as pure incantation: simply say the right words the right way, and, as the ancient Irish filid could tell you, the human mind can be ensorceled into believing nearly anything.

Try it: Crooked Hillary. Or Nancy Pelosi.

Do people really know why they’re supposed to hate them? No — unless it’s to recite other powerful though empty incantations, like Benghazi, Uranium One, or (shudder) San Francisco.

In TrumpWorld, it’s brands all the way down.

Democrats, being Democrats, are having a big argument right now about their new slogan, “A Better Deal.”

Is it on point? Does it suck? What do the polls say?

It doesn’t freaking matter.

Quick, now. What was Barack Obama’s slogan in 2012? George W. Bush’s in 2000 and 2004? Bill Clinton’s in ’92 and ’96?

You don’t remember. And it doesn’t matter.

Ah, but I bet you think you remember the Obama ‘08 slogan. “Hope and Change,” right? Actually he had at least four: “Hope,” Change,” “Change We Can Believe In,” and “Change We Need.”* They didn’t matter — until Obama made them matter.

You know what else doesn’t matter? Logos. Obama didn’t even like his now-iconic ’08 logo when he first saw it.

“It’ll do,” he said. And he was right. So would have lots of others.

People don’t vote for slogans. They don’t vote for logos. They vote for strong leaders who share their values.

Who fights over a slogan? Not leaders.

Fighting over the slogan — and all the related fussing over polls, focus groups, policy details — only signals voters that Democrats are obsessed with little stuff. Leaders are not obsessed with little stuff.

Leaders are focused on their vision of a better future, and they have the personal presence to inspire us with that vision.

It’s in that presence that leaders make their case. Democrats trying to figure out how to win need to stop trying to figure it out. They need to discover the world below their necks.

Then they might stumble across why Kentucky Congressional candidate Amy McGrath has exploded onto the national stage with her first campaign commercial. Holy smokes, there’s a leader.

Quick quiz: What’s her slogan?

Answer: Who cares?

*Want more presidential campaign slogan trivia? Here’s a list.

[Also published at Huffington Post.] White House counselor Kellyanne Conway and “Reliable Sources” host Brian Stelter had a widely anticipated debate Sunday about the fairness of media coverage of the Trump administration. On every point that came up, Stelter exposed Conway as, at best, misleading.

And yet to some viewers, she was the clear winner.

How? Stelter and Conway were playing entirely different games.

For Conway, the audience was President Trump and the 36 percent of Americans who still trust him. Speaking past Stelter and connecting with them, she followed the rules of a game defined back in the 60s by the media consultants of the 1968 Nixon for President campaign.

One of them was the eventual founder of Fox News, Roger Ailes. Here’s Ailes in 1970, explaining why Nixon was seen to have lost his 1960 TV debate with John F. Kennedy despite many people believing he had won on the merits:

I think that the lighting was bad. It was experimental at best and sloppily done. His makeup was bad. I think he was tired–and this may have shown in his reaction and response.

I think that before the debates, John Kennedy spent the entire day briefing himself and relaxing, concentrating on the TV encounter.

Mr. Nixon did not do that. He walked in and handled it as if it were any other telecast.

Mr. Nixon, in a sense, stuck to the old school of debating, looking at Mr. Kennedy. But Mr. Kennedy looked at the camera, because he was essentially talking not to his opponent but to the people at home, and he was able to establish a kind of communication between himself and the home viewer. [Emphasis added.]

Ailes, along with other media and advertising experts, coached Nixon to be far more effective on TV for his winning 1968 campaign, and during his time in the White House.

The rules they defined still apply, as you can see by analyzing the video of the Stelter-Conway interview. Let’s start with the splash frame from CNN.com:

Conway looks happy, relaxed, and confident, is well lit by studio lighting, and is wearing red, a power color.

Now let’s look at her in split screen with Stelter:

Oh oh. Just seconds in, and Stelter’s losing already.

How do we know? Let’s count the ways.

And so it goes throughout the interview. As Stelter tries to pin Conway down on one misdirection after another, she just moves blithely on to the next. And each of his sallies feels, I’m sorry to say, “low energy.” At pains to preserve the standards of civil discourse, he repeatedly reassures her of his respect, while she turns her responses into digs at him and CNN.

One example among many:

Stelter: “The scandals are about the president’s lies. About voter fraud, about wire-tapping, his repeated lies about those issues. That’s the scandal.”

Conway: “He doesn’t think he’s lying about those issues.”

It’s OK because he doesn’t think he’s lying? On the page, Conway’s response is ridiculous. But on TV, she looks and sounds unruffled and in control.

Stelter, on the other hand, comes across as alternately tentative, frustrated, and confused:

On TV, impressions are what matter much more than words — as Conway’s boss could tell you, you win by looking like you’re winning.

CBS correspondent Lesley Stahl has often told the story of how she learned this lesson from a Reagan administration official back in 1984. Here’s how she related it to Bill Moyers in a 1989 interview:

I did a piece that was-where I was quite negative, to be honest with you, about Reagan. And yet the pictures were terrific, and I thought they’d be mad at me, but they weren’t. They loved it. And the official outright said to me, “They didn’t hear you. Didn’t hear what you said. They only saw those pictures.” And what he really meant was it’s the visual impact that overrides the verbal.

And that’s what happened, yet again, here.

[Also published at Huffington Post.] Imagine if counterfeiting suddenly became legal. Say we asked people not to do it — but there would be no penalty if they did.

What would happen?

Simple: There would be an explosion of fake money. If people could buy things with currency worth nothing more than paper and some ink, many would, of course, do just that. Crooks would print up more and more counterfeit bills, which would start to take over from real money.

A venerable principle of economics explains why this happens. It’s named Gresham’s Law, after 16th century financier Sir Thomas Gresham.

The short version: Since sound money is expensive, and bad money is cheap, bad money proliferates and takes over the economy.

More recently, Gresham’s Law has been extended to information: Bad information drives out good, and for similar reasons.

In America in recent decades, an industry of information counterfeiters has sprung up, and it’s making a few, unprincipled people very rich, at the expense of everyone else.

And at the expense of democracy.

Bad money threatens the free market. But bad information threatens freedom itself. That’s because a vote is only as good as the information it’s based on. If your choices are based on illusions, what are they really worth?

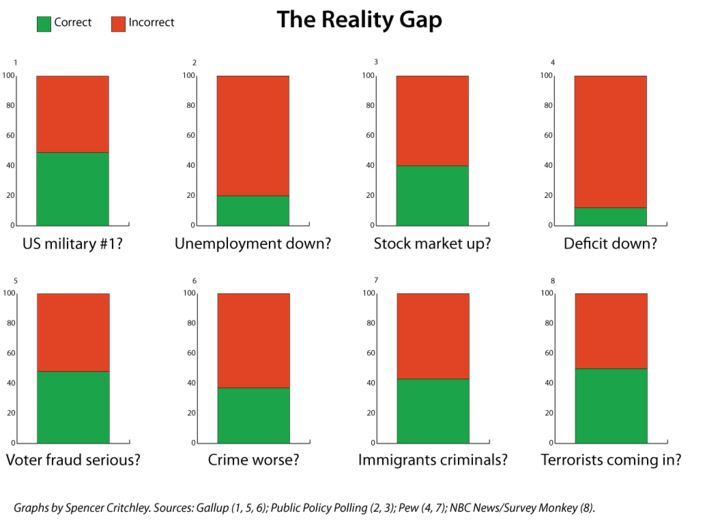

Much of our population now votes, and makes other crucial decisions, based on bad information. Much of what they think they know about the world is untrue.

In effect, they live in a prison of lies, one whose walls they can’t even see.

When Everything You Know Is Wrong

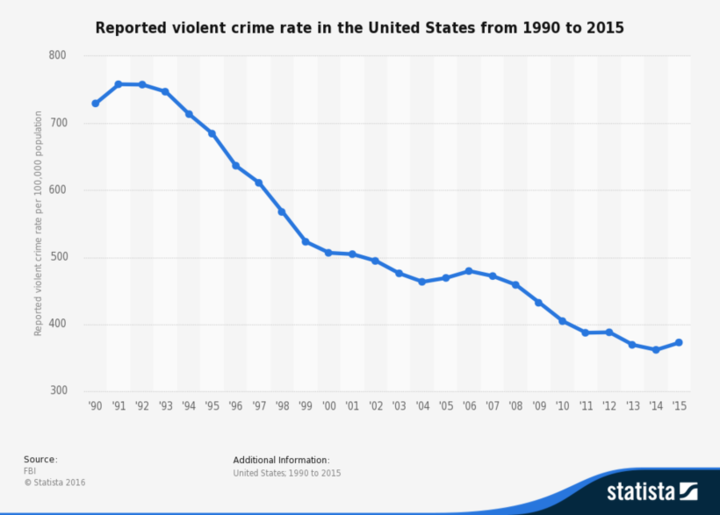

Given these terrifying facts, is it any wonder that Americans voted in 2016 for a candidate who promised to save us?

How could it have gone any other way? Hillary Clinton pledged to continue and build on the legacy of Barack Obama. How could any sensible person — any patriot — vote for that?

Except none of those “facts” was true. The voters who believed them were voting for and against illusions.

Think about what that means: the effect was the same as falsifying ballots. It’s just that the falsification happened before the vote instead of after.

Put another way, it’s like voters had a choice between door number 1 and door number 2, but for many of them, the numbers had been switched: door 1 was actually door 2, and vice versa.

Certainly there were people who voted for Donald Trump based on a more or less accurate picture of reality. But huge numbers — far more than were needed to swing the election — were just plain wrong about the issues on which they based their votes.

Let’s take another look at the “facts” these voters believed in.

Imagine if counterfeiting suddenly became legal. Say we asked people not to do it — but there would be no penalty if they did.

What would happen?

Simple: There would be an explosion of fake money. If people could buy things with currency worth nothing more than paper and some ink, many would, of course, do just that. Crooks would print up more and more counterfeit bills, which would start to take over from real money.

A venerable principle of economics explains why this happens. It’s named Gresham’s Law, after 16th century financier Sir Thomas Gresham.

The short version: Since sound money is expensive, and bad money is cheap, bad money proliferates and takes over the economy.

More recently, Gresham’s Law has been extended to information: Bad information drives out good, and for similar reasons.

In America in recent decades, an industry of information counterfeiters has sprung up, and it’s making a few, unprincipled people very rich, at the expense of everyone else.

And at the expense of democracy.

Bad money threatens the free market. But bad information threatens freedom itself. That’s because a vote is only as good as the information it’s based on. If your choices are based on illusions, what are they really worth?

Much of our population now votes, and makes other crucial decisions, based on bad information. Much of what they think they know about the world is untrue.

In effect, they live in a prison of lies, one whose walls they can’t even see.

When Everything You Know Is Wrong

Given these terrifying facts, is it any wonder that Americans voted in 2016 for a candidate who promised to save us?

How could it have gone any other way? Hillary Clinton pledged to continue and build on the legacy of Barack Obama. How could any sensible person — any patriot — vote for that?

Except none of those “facts” was true. The voters who believed them were voting for and against illusions.

Think about what that means: the effect was the same as falsifying ballots. It’s just that the falsification happened before the vote instead of after.

Put another way, it’s like voters had a choice between door number 1 and door number 2, but for many of them, the numbers had been switched: door 1 was actually door 2, and vice versa.

Certainly there were people who voted for Donald Trump based on a more or less accurate picture of reality. But huge numbers — far more than were needed to swing the election — were just plain wrong about the issues on which they based their votes.

Let’s take another look at the “facts” these voters believed in.

These are just some examples from the alt reality many Americans now inhabit. Among other false but popular beliefs that influenced voters in the 2016 election: Obama was a Kenyan born Muslim who was going to take away all our guns, FEMA planned concentration camps for conservatives, the U.S. military was going to invade Texas, and Hillary was the leader of a sex slavery ring run out of a Washington, D.C. pizza restaurant.

Since the election, most explanations of how Trump won it have focused on factors that might have accounted for, at most, a few percentage points each in state-by-state vote totals: interference by Russia and Wikileaks, Hillary’s emails and/or the media’s obsession with them, mistakes by Hillary’s campaign, disruptive comments by FBI Director James Comey, or the Democratic Party being too far right, too far left, or too disconnected from the white working class.

Some or all of these likely had an influence. But remember, Hillary lost by less than 78,000 votes [update: this replaces the earlier estimate of several hundred thousand votes with the final result] in three battleground states, while winning the popular vote overall.

Whatever the causes, her defeat was razor thin.

Now look again at the percentages in my eight examples: all the margins are in the tens of percentage points, and many represent strong majorities of the relevant voters.

That means that any of the most popular explanations for the election result shrinks to insignificance when compared with this one:

The misinformation industry threw our election.

How Lying Became a Multi-Billion Dollar Business

Believe it or not, there was a time when self-described journalists wouldn’t have been allowed to just make stuff up all day long without presenting opposing viewpoints. That time was before 1987, when the federal Fairness Doctrine was eliminated.

The Fairness Doctrine was a policy of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) adopted in 1949. It required broadcasters both to present important and controversial topics, and provide time for opposing viewpoints.

It was based on the idea that the public owned the airwaves. Broadcasters had licenses to use this public property, but not to abuse its owners by misleading them.

But that rule went away in 1987, as part of deregulation under the Reagan administration. Conservatives thought the Fairness Doctrine impinged on free speech, and that free market competition would take care of fairness.

Unfortunately, the effect was like removing all guarantees behind a currency.

Peddlers of information were now free to sell fiction as fact, like counterfeiters printing their own money. And just like counterfeit money, misinformation is really cheap to produce, and has a huge market.

Emotion sells. If you’re not required to tell the truth, you can just make up addictively provocative stuff, all day long. And since you don’t need to put any time or money into actual reporting or fact-checking, it costs you next to nothing to churn it out and rack up the revenues.

And what do you know, after 1987 right wing talk became the top commercial talk radio format in the U.S. Further deregulation made the format particularly lucrative, by allowing the formation of conglomerates like Clear Channel. They could afford to pay big syndication fees to the most popular hosts, led for many years by Rush Limbaugh, who got very rich by making his listeners very angry. Not surprisingly, Rush inspired imitators: Glenn Beck, Sean Hannity, Alex Jones, Michael Savage, Mark Levin, and many more.

TV’s turn had to wait for the arrival of digital cable and satellite technologies, which brought a proliferation of channels, along with the need to fill them with content. That enabled Rupert Murdoch’s 1996 creation of Fox News, which quickly began its rise to number one among basic cable channels.

As with right wing talk radio, Fox isn’t really in the news business, but a news-like form of the entertainment business. Despite its (possibly deliberately) ironic slogan of “Fair and Balanced,” what Fox sells is sensation, with objective information playing a distinctly secondary role.

There are legitimate reporters at Fox. But the network’s cash cows are the heavily biased, highly provocative opinion shows, like Fox and Friends, Hannity, and the industry-leading O’Reilly Factor.

New technologies also enabled the right-wing web. The introduction of the graphical Mosaic browser in 1993, followed by easy site-building tools and the rise of cheap bandwidth, meant almost anyone could be a publisher. Soon enough, that came to include hot button-pushing “news” sites, from the Drudge Report, to InfoWars, to WorldNet Daily, to Breitbart, to who knows how many more.

There was money in all of it — a lot of money.

In 2016, Forbes magazine ranked Rush Limbaugh the world’s 10th highest-paid celebrity, with an estimated income of $79 million. His net worth is variously estimated at between $350 million and $500 million.

Fox News’ 2015 revenue was projected at $2.3 billion, and the 2016 number will no doubt turn out to have been even higher, given that Fox broke ratings records on the back of the most attention-grabbing election campaign ever. Forbes estimates the net worth of Rupert Murdoch, who also owns other major media properties, at $13 billion.

In 2012, Business Insider’s Henry Blodget estimated that the Drudge Report was earning $50,000 a day, and that founder Matt Drudge must be worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Blodget made this startling comparison:

In short, the Drudge Report is almost as big a digital media property as The New York Times.

That’s absolutely staggering.

Why?

Because The New York Times is produced by ~1,200 journalists. The Drudge Report is produced by one.

Blodget is exaggerating a bit here: earlier in his article he estimates the total Drudge staff at “maybe three.”