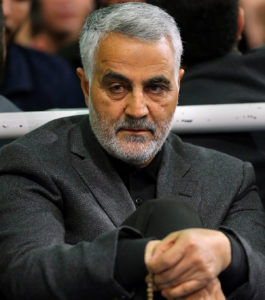

One overlooked aspect of the apparently impulsive and reckless decision to kill Qassim Suleimani: how evil is enabled by bureaucracy.

In this case, according to reporting, Trump’s advisers presented him with “bracketed options,” a common bureaucratic tactic. Bracketed options are designed to manipulate the recipient into choosing what the presenters want.

It’s a Goldilocks process: offer one choice that’s too far one way, another that’s too far the other way, and one in the middle that’s “just right.”

The trouble this time: these bureaucrats were dealing with Trump, who thinks at the level of an emotionally disturbed child. And he chose the most extreme option. He wasn’t supposed to, it was only there to nudge him towards another one, but he chose it.

It’s not that Suleimani didn’t have it coming. He was a brutal terrorist who could be targeted under the standards of just war, depending on the circumstances. But Trump appears to have risked chaos — death and suffering for untold numbers of people — with little more than a moment’s thought. If so, even if it somehow works out, this will still have been a grotesquely irresponsible decision.

“Top Pentagon officials were stunned,” according to the New York Times.

First of all, how could they possibly be stunned? Did they forget it was Donald Trump they were dealing with? An incredible lack of foresight for people we trust to plan wars.

But also, this was a typical example of bureaucratic dishonesty — one that happened to backfire terribly — found throughout government and in the private and nonprofit sectors too: anywhere that people are incentivized to diffuse accountability while their self-interest remains concentrated. Note that as stunned as Trump’s advisers were, none was too stunned to stick with the program — or lack of program, in this case.

Not every bureaucrat is dishonest, of course. Some are positively noble, like the courageous impeachment investigation witnesses who have risked their careers, and even their personal safety, in the service of truth and duty. And many just quietly and anonymously do their best.

But the incentives of bureaucracy encourage the ignoble. Stand up for the right thing and risk your livelihood? Or keep your head down and try to work the system?

Under these conditions, too often it’s the worst people who rise to the top: those who are the most skilled at pursuing their own interests while hiding them, behind a deliberately bland countenance.

This studied boringness can an asset, since it deflects attention from what’s really up. Attorney General William Barr is an exemplar. Watch any of his public defenses of the indefensible. Words, tone, body language: all say, “Nothing to see here.”

But we may not need a Barr. Evil can happen passively, just because it’s allowed to happen, just because no one is on the hook.

Either way, much of the evil done in our world has no apparent evil-doer. It seems to be born from the void, and so it is.

The void may be the absence of accountability, or it may be the void at the core of a deliberate schemer like the nihilistic Barr. When asked recently if he worries about the damage he’s done to his reputation, he answered, “Everyone dies.”

As Hannah Arendt says in “On Violence,” “The greater the bureaucratization of public life, the greater will be the attraction of violence… for the rule by Nobody is not no-rule, and where all are equally powerless we have a tyranny without a tyrant.”