As we risk obliviously repeating catastrophic mistakes others have already made, some thoughts about memory and freedom, from people who know the precious value of both…

Most of us in the U.S. have been spared the necessity of knowing history, and instead have been able to live as if the world was created at our birth. But people in Central and Eastern Europe have already been trammeled by the history that has just now caught up with us. They’ve been trying to warn us for decades.

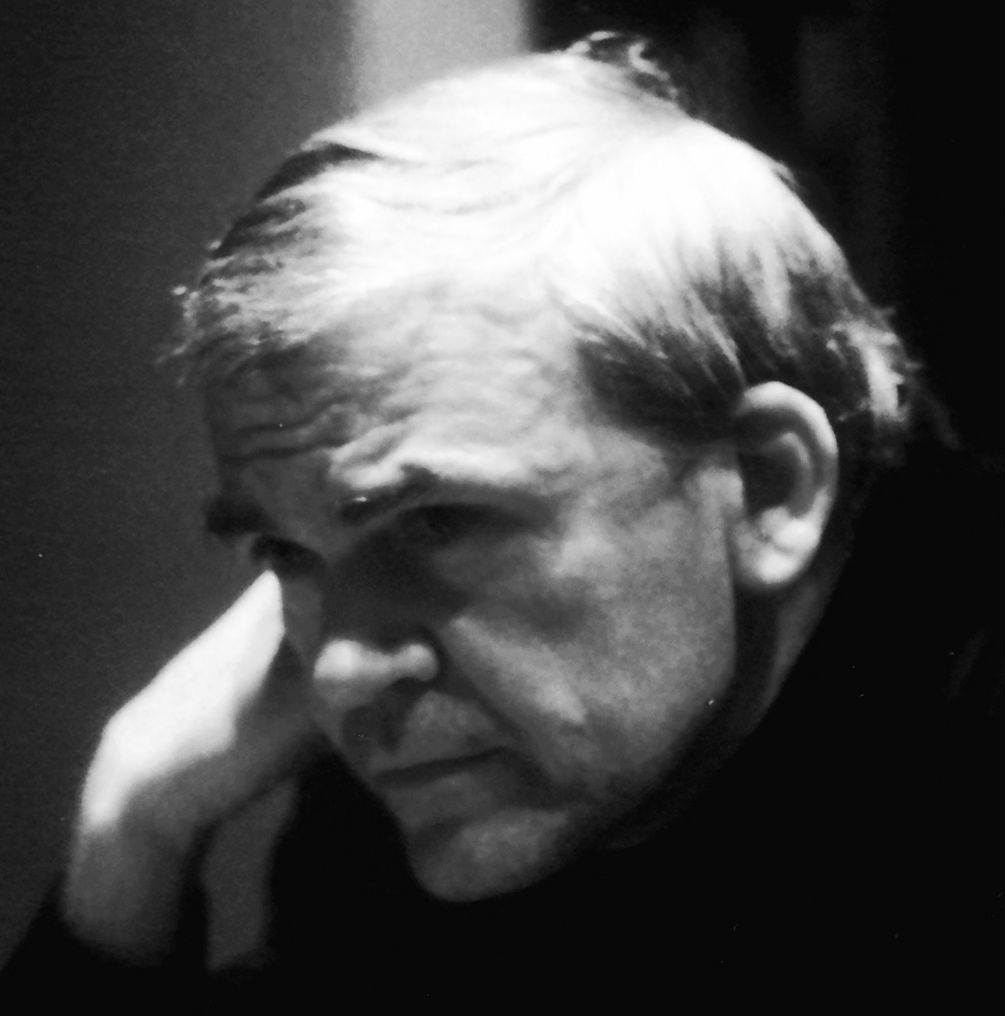

This is from the Czech writer Milan Kundera’s The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, published in 1979 (emphases mine):

If Franz Kafka is the prophet of a world without memory, [Russian-controlled President] Gustáv Husák is its builder… [H]e is called the President of Forgetting.

The Russians put him in power in 1969. Not since 1621 has the Czech people experienced such a devastation of culture and intellectuals. Everyone everywhere thinks that Husák was merely persecuting his political enemies. But the struggle against the political opposition was instead the perfect opportunity for the Russians to undertake, with their lieutenant as intermediary, something much more basic.

‘I consider it very significant from this standpoint that Husák drove one hundred forty-five Czech historians from the universities and research institutes. (It’s said that for each historian, as mysteriously as in a fairy tale, a new Lenin monument sprang up somewhere in Bohemia.) One day in 1971, one of those historians, Milan Hübl, wearing his extraordinarily thick-lensed eyeglasses, came to visit me in my studio apartment on Bartolomejska Street. We looked out the window at the towers of Hradcany Castle and were sad.

‘“You begin to liquidate a people,” Hübl said, “by taking away its memory. You destroy its books, its culture, its history. And then others write other books for it, give another culture to it, invent another history for it. Then the people slowly begins to forget what it is and what it was. The world at large forgets it still faster…”

‘Was that just hyperbole dictated by excessive gloom? Or is it true that the people will be unable to survive crossing the desert of organized forgetting?’

Sound familiar?

Central and Eastern European writers who experienced authoritarianism are a precious resource for us now — if we don’t just forget about them.

A couple of others we must remember:

Vaclav Havel, as in his historic essay “The Power of the Powerless,” about how a “posttotalitarian” system succeeds by simply training people to accept pervasive dishonesty — how many of us do that every day?

Individuals need not believe all these mystifications, but they must behave as though they did, or they must at least tolerate them in silence, or get along well with those who work with them. For this reason, however, they must live within a lie. They need not accept the lie. It is enough for them to have accepted their life with it and in it. For by this very fact, individuals confirm the system, fulfill the system, make the system, are the system.

Csezlaw Milosz, author of The Captive Mind, an account of life under occupation occupied by Nazi Germany and then the Soviet Union. Milosz describes how even highly educated, independent people willingly embrace tyranny, one convenient step after another:

One compromise leads to a second, and a third, until at last, though everything one says may be perfectly logical, it no longer has anything in common with the flesh and blood of living people.

To keep freedom alive, we have to remember what it’s like, day by day.