Words matter. And if Democrats aren’t careful, they’ll use them to lose the 2020 election.

Led by popular figures like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Bernie Sanders, some on the left are calling themselves Democratic Socialists.

Are they really? I hope not. I hope what they really are is Social Democrats, and what we have here is just a confusion in terms. But either way, it hands Trump and his re-election campaign one of the best weapons he could hope for, and one of the only effective ones he’ll have.

Here’s the difference between “Social Democrat” and “Democratic Socialist,” and why it matters.

A Social Democrat is basically what we’ve traditionally thought of as a progressive: someone at the left edge of the mainstream of American politics, and closer to the center in many other Western democracies — familiar, friendly, and prosperous places like Canada and Britain. They favor more regulation and higher taxes than do many Americans, but like most Americans, Social Democrats believe in free markets. Meanwhile, nearly all Americans support some degree of socialism along with their free market, in the form of services like Medicare, Social Security, public roads, or a taxpayer-funded military.

So what’s a Democratic Socialist? I suspect many of those who think they are one assume it’s about the same thing. But no. Democratic Socialists are, as the name states, actual, full-on socialists.

They believe in centralized control of the economy, as Marquette University sociologist Michael McCarthy explains (approvingly) in the Jacobin: “Democratic socialism, on the other hand, should involve public ownership over the vast majority of the productive assets of society,”

Given the rampant inequality generated by the last few decades of deregulated capitalism, apparently this sounds like a pretty cool idea to a lot of people now. The trouble is, it turns out to be really bad policy.

Whole-hog, centralized-control socialism is an experiment that has been run, and it’s an experiment that has failed. Don’t take my word for it. Take the word of the formerly socialist countries who’ve abandoned it — like, say, Russia and China — or the Nordic countries, which went part of the way there and chose to stop.

The reason has little to do with whether or not we think wealth should be shared more fairly. It has everything to do with complexity.

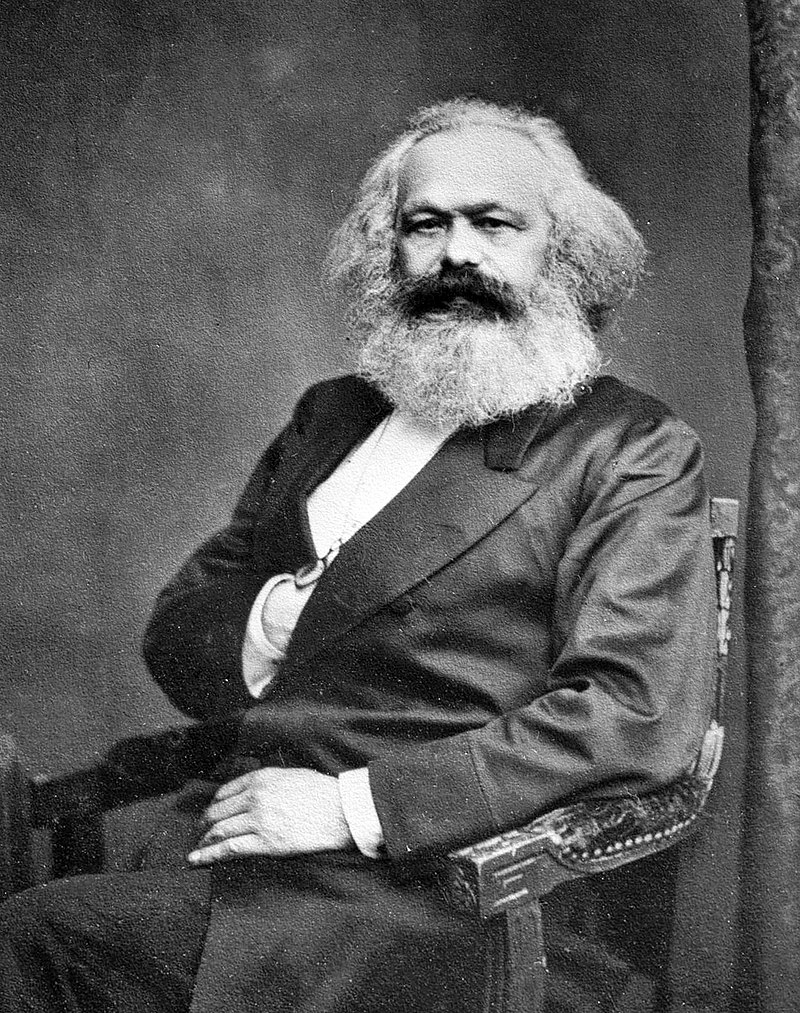

The idea that a modern, complex economy could be run under centralized control is an artifact of the 19th Century. It was born out of the rise of science and the Industrial Revolution. Karl Marx based his economic analysis in large part on the new mechanical technologies he saw transforming the world around him, for good — for capitalists — and for bad — for workers, like those he saw suffering in the nightmarish slums and factories of England.

Marx, also drawing on Hegel and other sources, thought he had discovered the science of history, and therefore that history could be predicted. What he couldn’t see was that the linear processes of machinery — this switch trips that lever, which releases that blast of steam — don’t begin to encompass the nearly infinite complexity of the interactions of millions of humans.

And since Lenin established the first one, in the Soviet Union, centrally planned economies have failed to control complexity, five-year plan after five-year plan. It turns out reality refuses to play ideological ball, unless it’s forced to.

And that leads me to the second big problem with full socialism: if we really want the government taking over most of the economy, we’re going to have to accept a lot of coercion — and we’ll need to cut back the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution.

None of that is likely to be popular with most Americans.

And that’s why Republicans, and Trump in particular, are so delighted when they hear Democrats calling themselves socialists, instead of leaving that to GOP attack ads.

We can only hope it doesn’t become any more fashionable.

As the historian and socialist-turned-Social Democrat Tony Judt said towards the end of his life, in “Thinking the 20th Century,” the biggest story of that era was “how so many smart people could have told themselves such stories with all the terrible consequences that ensued.”