[Also published at Medium.] With the Liberation of France in 1944 came a miraculous discovery: the entire nation had resisted the German occupation.

“Paris liberated! Liberated by itself, liberated by its people with the help of the French armies, with the support and the help of all France, of the France that fights, of the only France, of the real France, of the eternal France!” proclaimed General DeGaulle in his victory speech.

It was an inspiring story of courage and resolve. If only it had been true.

But no. The story of universal resistance was a comforting fiction, hiding a complicated and painful reality: while there certainly had been heroic resisters, most of the French had silently cooperated with their occupiers and the puppet Vichy regime. Many had actively collaborated.

What story will we tell, when our time comes? Because the Trump presidency will end, and for many, that will be a time of shame.

Not, of course, the ones who have no shame. But those who see Trump for what he is, and yet remain silent. They mimic the French attentistes, who privately deplored the occupation, but chose to “wait and see.”

When the wait was over, though, it turned out they couldn‘t bear to see.

So they turned to an alternate reality, in which courage was redefined. In an essay for The Atlantic at the end of 1944, philosopher Jean Paul Sartre hailed the heroes of the “Silent Republic.” Their contribution? They could have informed on actual Resistance members, but didn’t.

Some tried to puncture the nation’s self-delusion. In 1947, novelist Jean-Louis Curtis published “The Forests of the Night,” a portrayal of wartime life in a typical French village. As Curtis wrote, resistance was the “rather blurred background” to a far less noble foreground: acquiescence, collaboration, and betrayal.

Curtis’ book won France’s top literary honor, the Prix Goncourt. But it failed to displace the more less realistic fiction his compatriots preferred.

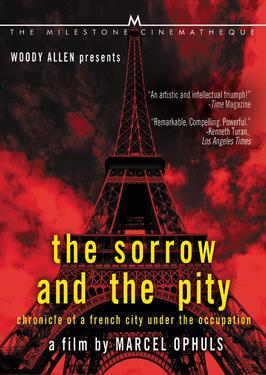

A full reckoning with the truth didn’t begin until 1969. That was when film-maker Marcel Ophüls released his quietly harrowing documentary “The Sorrow and the Pity” — which was banned from French TV until 1981. The full meaning of that title is revealed through the first-person accounts of a few brave resisters—and many others who struggle to explain their wartime behavior even to themselves.

“There was one value that we all shared, and that was caution,” offers one.

“I’m trying to remember, but I can’t,” says another.

But the archives did remember. Historian Thomas Paxton studied them exhaustively and, two years after “The Sorrow and the Pity,” he published his findings in “Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order” (1971): most people, some of them eagerly, had aligned with whomever was in power.

A crude graph of French public opinion from 1940 to 1944 would show nearly universal acceptance of Marshal Pétain [head of the collaborationist Vichy government] in June 1940 and nearly universal acceptance of General de Gaulle in August 1944, with the two lines, one declining and the other rising, intersecting some time after… November 1942 [after the Allies landed in North Africa and the Germans occupied the former “Free Zone” of southern France].

After Paxton, assessments of the true strength of French resistance would shift this way and that. But the current judgment of history incorporates the pain of that very uncertainty. As Ronald C. Rosbottom writes in “When Paris Went Dark” (2014):

Even today, the French endeavor both to remember and to find ways to forget their country’s trials during World War II; their ambivalence stems from the cunning and original arrangement they devised with the Nazis, which was approved by Hitler and assented to by Philippe Pétain, the recently appointed head of the Third Republic, that had ended the Battle of France in June of 1940. This treaty—known by all as the Armistice—had entangled France and the French in a web of cooperation, resistance, accommodation, and, later, of defensiveness, forgetfulness, and guilt from which they are still trying to escape.

This web waits for us.

It’s popular to scorn and mock the wartime French. A supposed French propensity for surrender has become a stock joke (one that ignores World War I and much other history).

But who are we—especially the silent ones among us—to laugh?

To speak out against the German occupation was to risk torture and death.

To speak out against Trump—so far at least—is to risk only embarrassment, strained relationships, or perhaps the loss of some business.

Before we judge the French of World War II, we must ask ourselves if we can honestly say we would have done better. With that in question, their warning should sound all the louder in our ears.

If they felt such shame, how will it be for those of us who find mere inconvenience an excuse to forsake democracy?

And make no mistake, that is what it means to stay silent now, as Yale historian Timothy Snyder, for one, argues so persuasively and concisely in On Tyranny.

When the institutions and norms of democracy are strong, they protect us. But when they are threatened, as elections, the judiciary, law enforcement, the press—and even the truth itself—are threatened now, we are called to protect them.

For most of us, most of the time, democracy is easy. Maybe too easy. We’ve grown awfully comfortable letting a tiny minority serve as its guardians, out of sight, out of mind.

But ultimately, each of us is democracy’s last line of defense. And silence, unavoidably, becomes betrayal.

It’s that hard knowledge which met the attentistes of post-war France. So too the attentistes of post-Trump America.

Speak out, now.